China’s most popular microblogging site, Sina Weibo, employs around 150 censors, 24 hours a day, their mission being “to delete any post on Sina Weibo deemed offensive or politically unacceptable.” This is no small task, given that the site, run by Sina Corp, has over 500 million registered users (Reuters).

“Weibo is easily the most intriguing feature of China’s media landscape,” writes The Atlantic, and is a platform where “the possibility of political subversion is real.” The Twitter-like service has altered China’s media landscape even without factoring in political posts: when a high-speed train collision killed 40 and injured hundreds back in 2011, the government ignored the incident — until “tweets and photos on Weibo forced them to acknowledge what had happened.”

Who is actually behind the constant management of posts (a result of the ruling Communist Party’s censorship)? Recent college graduates – all of them male – who work long hours for little pay to keep Sina Weibo’s posts in line with accepted restrictions. According to Reuters, “Internet firms are required to work with the party’s propaganda apparatus to censor user-generated content.”

Reuters recently spoke to four former censors at Sina Weibo (no current censors would consent to interviews). One of the censors – each of whom had quit within the past year, generally citing poor career prospects and little pay – said that “People are often torn when they start, but later they go numb and just do the job.”

However, not all censors see their role in a negative light: “Our job prevents Weibo from being shut down and that gives people a big platform to speak from. It’s not an ideally free one, but it still lets people vent,” another former censor told Reuters.

Here’s how the process works:

- Sina Weibo’s computer system scans each microblog before it’s published

- a “fraction” of these posts are marked as sensitive and read by a censor

- the censor then decides whether to delete it

- posts with “must kill’ words (references to banned groups, etc) are blocked and manually deleted

- censors update lists of sensitive words as bloggers create new expressions to avoid censorship

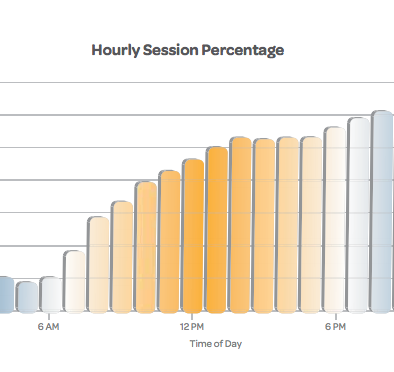

Over an average 24-hour period, censors process about 3 million posts. On an average day, 40 censors work 12-hour shifts, each one working through a minimum of 3,000 posts her hour. More censors are employed during busy times, usually “sensitive” anniversaries of political events (Tiananmen Square) or major political events happening in realtime.

A March 2013 study of censorship on Sina Weibo found that “deletion times were found to be significantly shorter for a subset of users who tended to post deleted content most often, an indication that Sina Weibo actively monitors the activity of some users.” Meaning that Sina Weibo censors are not only searching for flagged keywords, but also watching the posts of specific individuals.

What happens once a post is deleted? In many cases, censors block the posts from other users but not from the author, so the author is unaware that the post was censored. Censors also have the ability to block a user’s ability to make comments, or even to shut down their account.

Finally, what about those posts that sneak past the censors? If it is widely disseminated, the government can pressure Sina Corp to remove the post, and/or punish the censor responsible for letting it through, with fines or dismissal. Post authors can be charged with defamation “if online rumours they created were visited by 5,000 Internet users or reposted more than 500 times.”

While we’ve all seen content on Twitter that’s useless, inappropriate and even offensive, in the end users are free to post what they choose – regardless of references to religion, race, sexuality, or political leanings. In the aftermath of outcries against hate speech on the platform, this past August Twitter did update the platform’s rules and provide an in-tweet report button for abuse, because “people deserve to feel safe on Twitter.” Other social platforms, including YouTube, Google, Instagram and Facebook, also have measures in place to identify and block hate speech.

But there’s a huge difference between having a reporting system in place for users to flag hate speech, and having a team of censors employed to keep the messages on a social network in line with government restrictions. Will the pervasiveness of social networks help to erode the government’s tight hold over media and communications in China?